Terrorists' bombs never shattered this

victim's belief in God -- or the future

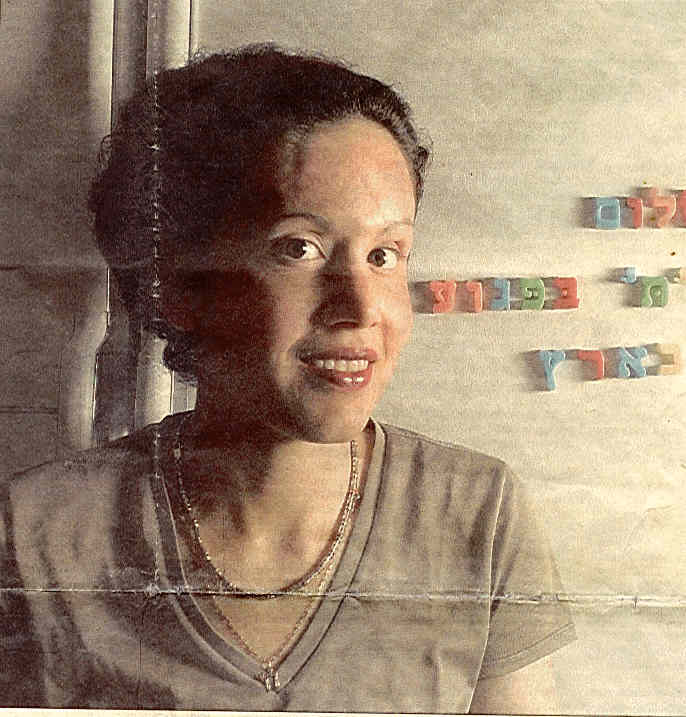

Diana Campuzano

She'd been in Jerusalem for more than three weeks, studying at a woman's yeshiva, a college of Jewish learning.

In two days Diana Campuzano, who'd grown up in the town of Greece, New York, expected to fly home to New York City and her sales job at Henri Bendel, a swank women's clothing store.

Needing gifts to bring back to friends, she set out for the shops of Ben Yehuda Street. The afternoon was gorgeous, she recalls, sunny and warm.

At an outdoor cafe she saw Gregg Salzman, an American from her youth hostel, sitting with his friend Sherri Wise, a dentist from Vancouver.

Diana (pronounced "Dee-AH-na"), joined them for lunch. As she was finishing her vegetarian lasagna, Sherri said, "Look, there's a man dressed as a woman."

By the time Diana turned around, all she could see was a retreating figure in a flowered yellow dress, strolling across the open-air plaza with two packages in his arms.

"I was thinking what an odd sight that was in Israel, a man in drag," recalls Diana."

Ten minutes later came the first explosion. At 3:09 on the afternoon of Sept. 4, 1997, a suicide bomber blew himself up 10 feet in front of Diana.

Seconds later a second bomb went Off 12 feet from her, then a third - the man in the flowered dress - 25 feet away.

Three deadly bombs, three suicide bombers.

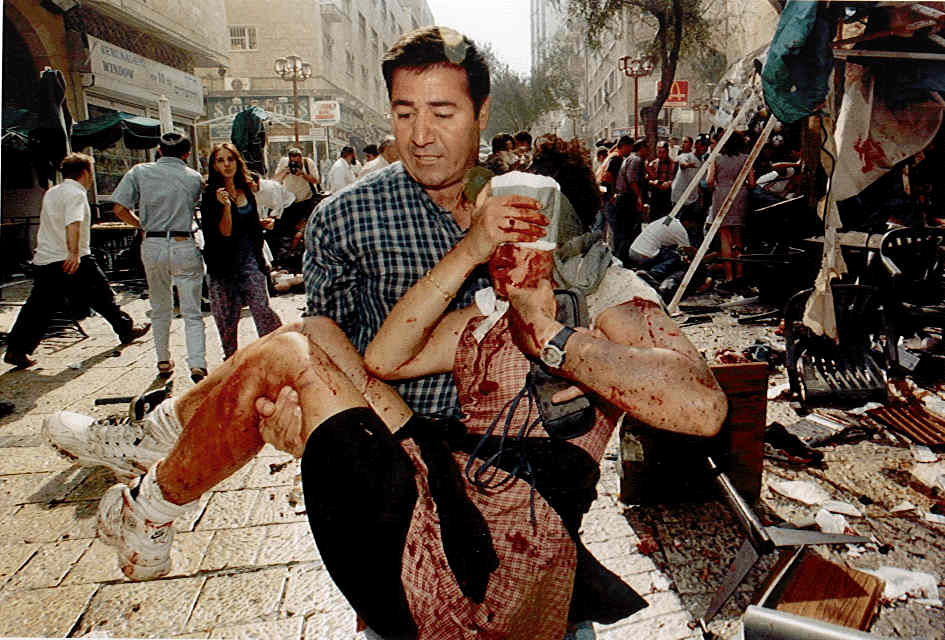

Diana being carried from the scene of the carnage

The next morning's headline in the Democrat and Chronicle would read, "Hamas bombs kill 7, hurt 192."

In the days to come, two of those hurt would die. Second on the list of most critically injured was Diana, skull fractured, breathing with the help of a respirator and assumed blind, both eyes filled with blood.

She would spend the next three weeks lost in a fog of morphine and methadone.

In late October she would fly home to Greece with her parents, to recover.

Since then, Diana has endured one surgery after another to repair her broken face, and countless dark nights of the soul.

But the past 11 months also have been a time for soul-searching -- a time for her to re-examine who she is, to resolve tensions with her parents, to reach for a greater peace with her God.

When Ben Yehuda Street stopped reverberating that afternoon, the three friends were injured but conscious.

The first bomb had picked up Gregg and hurled him 8 feet away. Passersby recoiled from him as he ran from the site: He was covered with the bomber's blood. Then someone offered him water and he was taken away to the hospital.

Sherri, burned over 30 percent of her body, also was coated in the bomber's blood -- and skin. When she stumbled to her feet, she could see the scattered bodies and the bomber's leg and still-beating heart on the stone pavement.

And she could see Diana, blood pulsing from her forehead, her nose gone.

"All I remember is looking at Gregg one minute and falling to the ground in complete darkness the next, like someone hit a light switch," Diana, now 33, says over breakfast on a summer morning near her home.

She's wearing sweats and silver hoop earrings. A Hebrew letter "chai" (symbolizing life) dangles from a long silver chain around her neck. She wears, backwards, a baseball cap featuring South Park's Stan, his green plastic vomit pouring over the bill.

Dark red polish tips her expressive hands, the left one bearing the scars of burns.

"I just remember not being able to see a damn thing and feeling the blood pour down my face. . . . And all I could do was scream, 'I need a doctor! I need stitches!"'

In the ambulance, headed for Hadassah-Ein Karem Hospital, "I was still clueless about what happened. I thought some boys were playing ball and I'd gotten hit. I felt my face and my broken forehead, and my hands and feet were numb."

For seven hours, the surgeons removed bone slivers from her brain, reconstructed her nose and rebuilt the front of her skull with artificial bone, titanium rods and screws. Two of her sinuses had been destroyed, along with several major nerve endings for smell and taste on her left side.

Diana remembers nothing of the next weeks. But her parents do.

On the evening of the bombing, someone named Ezra repeatedly called collect from Israel to Diana's father in his Greece home." 'I don't know any Ezra,' I kept saying," recalls Ramiro Campuzano." I was sure he had the wrong number. We had absolutely no idea that she was in Israel."

The next time the operator called, he could hear Ezra yelling, "Tell him it's about his daughter." Ramiro accepted the charges.

Within minutes, he got a call from the U. S. State Department confirming the news.

He managed to reach Diana's doctor in Jerusalem." Should I come?" he asked." I can't make the decision for you," she answered." But Diana's on a respirator, she's had a craniotomy (reconstruction of the skull) and we don't know if there's going to be brain damage."

Two days later, he was on an airplane to an ancient land he had never expected to see, "All the way over, I kept saying to God, 'I know this is bigger than me and it's in your hands. Please guide me to do the right thing and help Diana come out of it."

Mabel Campuzano, Diana's mother, was in a hotel the night of Sept. 4, traveling through Utah with Diana's brother, Jorge, when she happened to catch a CNN report on the bombings.

"I felt so badly for those people," she recalls." I saw a picture of a girl on a stretcher and said, 'Lord, that shouldn't happen. ' Little did I know it was my daughter."

The next day, as the two stopped at another motel, they had a message to call home. Her husband told her the news. The following morning, Mabel saw a photo in USA Today.

Though her daughter was misidentified as an Israeli, her mother recognized Diana's legs, arms and hands as she was carried, bleeding, from the scene." 'That's her,' I said. 'How do you know?' my son asked. 'Doesn't a mother hen know her chicks?'"

"I kept thinking, 'Why did it have to be her?' But I believe there is a higher power and I'm not supposed to question Him."

It took a day and a half, after she woke up in the hospital, for Diana to force herself to look in a mirror.

"When I did, I was shocked but numb at first. Then I broke down and cried."

For the next five weeks, she lost weight and played a lot of Scrabble with her parents, "my dad losing every time." She couldn't see much out of her right eye, so her parents read to her -- biographies and novels, not newspapers.

Diana, who speaks Hebrew fluently, admits she "drove the nurses crazy."

Her father was even more critical of the hospital staff.

"I explained that Israelis are in-your-face people," Diana recalls." It sounds like they're yelling, but they're just talking."

Still, Ramiro insists he's "never seen anything like it. They're a tough bunch. I finally learned if you want something, you have to yell and scream the way they do."

Three times he asked nurses to change Diana's catheter.

"I finally pounded on the counter of the nurse's station." 'OK,'" they said." Nobody got upset or argued. They just took care of it."

During their goodbyes, her hospital social worker told Diana, "From the day you got here, you've been as stubborn as a mule, always complaining: You wanted water, you couldn't see. That's how I know you'll recover."

Recovery, however, would take time, and Diana couldn't do it alone in her apartment in New York City.

She came back to Rochester, New York, with her parents, napped for a couple of months and saw a Buffalo, New York, neurosurgeon about the air bubbles in her head.

She had to learn to be patient -- and to live in a home no longer her own.

"In New York City, I was always working, working out, taking classes," she says.

"Now I'm home for the first time in years, I'm not allowed to drive, and it's hard to depend on my mother to take me places."

She'd left home in 1983, after graduating from Greece Arcadia High School, where she was an A-student and, she says, "kind of shy."

Her parents, originally from Colombia, came to the area in 1973. Her father, armed with a new master's degree from Purdue University, was hired as an engineer for Eastman Kodak Co.

Diana, too, went to Purdue to study engineering. But soon found that the field was not for her. She worked as a flight attendant, a rental agent, even a T-shirt painter before finding a job retailing.

She moved to Boston, married a college beau, went on to New York City, divorced in 1993.

Her longtime affinity for Judaism dates back to high school:

Though she knew no Jews personally, she would find herself defending Israel. "And it really bothered me when people would attack the Jews."

Living alone New York City, she found herself thinking more seriously about Judaism.

"I tried to suppress it because my mom is a born-again Christian and I didn't want to hurt her," Diana says.

But eventually she went "rabbi-shopping," and forged a bond with Rabbi Allen Schwartz of Ohab Zedek, an Orthodox synagogue in Manhattan. Together they embarked on the long road to conversion, which she hopes to finalize this fall.

"None of what's happened to me has changed my feelings about Judaism," she says." And Israel has been good to us."

Since Diana's injury, the Israeli government has paid for everything: planes, hotels, surgeries, follow-up care.

"In their book" she says, "I'm a victim of war."

Someday, she says, she'll go back. But for now she needs to heal, and the process isn't easy for any of the Campuzanos.

"My mom's a very good person and smart, but when she doesn't understand what I'm trying to say, it drives me nuts," Diana says.

And though she adores her dad, "We're so much alike, we get on each other's nerves."

For Mom, the feelings are often mutual.

"I felt betrayed as a mother, that she wouldn't tell us she was in Israel," says Mabel.

"We knew she was taking classes. Why wouldn't she trust in us? But I decided she is my daughter and I love her dearly and I have to be there for her . . . and I believe everything happens for a reason."

As born-again Christians, Diana's parents live with a powerful faith -- and a fear.

"We believe that the way to get to heaven is because you believe in Jesus Christ who is the true messiah who died for our sins," Ramiro says.

"Diana does not believe that, and, as her father, I'm concerned about that."

"Even before her Jewish belief, she didn't visit much," he adds.

"Only now I'm beginning to understand who she is, who she's become as a woman."

The sight of blood, he adds, used to make her faint. Today she submits herself to these surgeries with such immense courage, beyond whatever I thought she was.

In June, Diana returned to New York City for a friend's wedding.

It was a hard trip.

On the street, some people stared at her face." I finally said, 'OK, fine, so I was in an accident. So stop staring. '"

Others meant well but hurt her just as much.

"People who knew what had happened, who I'd been avoiding for 10 months, would look at me and say, 'You look great -- considering what you've been through." '

Returning to Rochester, Diana made a choice:

"I want people to relate to me as me, not my problems. And since it may take two months, six months, a year, before I'm much better, I can either be depressed or enjoy my life as much as I can."

Recalling Deuteronomy 30:19 "Choose life that you and your children may live" - she chose life."

The life Diana has chosen to enjoy has no taste or smell. Sounds are muffled; vision is blurred in her right eye. Since the initial surgery in Jerusalem, she's had three operations -- on her nose, eyes and eardrums.

Still to come: Some "hardware" (the four screws barely visible through the skin) must be removed from her skull, the artificial bone adjusted, the orbit of her left eye socket filed down to match the right.

In another year, there may be plastic surgery to remove scars on her forehead.

"She was an acute blast injury victim, totally blind in one eye, who'd just had a near-death experience," recalls Dr. Ernest Guillet, a Brighton retina specialist who treated Diana.

"I would never have predicted 10 months ago that she'd be able to recover 50 to 75 percent of her vision -- so far."

For "a driven person, someone who had her life totally under control before this happened," Diana's loss of independence has hit hard, he says.

"I just reminded her how far she's come, physically and psychologically."

Sherri Wise, Diana's lunchmate on that fateful day, is still coping, too. The burns on one arm, in particular, still bother her, occasionally getting in the way of her work as a dentist.

The perforations of her eardrums are still healing; she's lost half the hearing in her right ear. She still has nightmares about what she saw that day.

"Diana has proven herself to be strong and a survivor," Sherri says in a telephone interview from Vancouver." It's partly her strength and belief in God that helps me get through.

"I'm close to lots of people, but only two can I call and they'll know how I feel. The three of us have an incredibly strong and lasting bond."

Gregg Salzman calls this bond "kesher," Hebrew for "connection." And his scarred arms are "just enough to remind me."

Yet he, too, remains drawn to Israel, where he hopes to spend the next few years establishing a chiropractic practice and a family.

"When I think of Diana, I think of someone who is extremely brave and very, very intelligent, a very deep person," says Gregg, who saw her again in April, by phone from New Jersey, "She has a profundity now, a sensitivity that wasn't there before."

Although her doctors are more than pleased with her progress, Diana isn't satisfied. And her self-consciousness keeps her from dating.

"I look in the mirror and realize I may never look the same, and I'm not comfortable with my face. I want it fixed yesterday."

But she and her parents believe They are on God's timetable, not their own.

"I believe it's God's plan for us," says Mabel." We hadn't seen her much before this, and I guess we have been closer since it happened. It's hard that this had to happen to her to have her come home. But, in a way, it's been a blessing."

Ramiro repeats a Spanish saying from his youth." No hay mal que por bien no venga:" Bad things happen for a good reason.

"God is saying to me, 'Ramiro, come closer to your daughter. Be a family again. '"

Adds Diana, "I don't know . . . why God let me live and not those others. But I do know God does things to people to bring them closer to Him . . . The doctors' hands can only do so much. The rest is in God's hands."

Still, in some ways Diana is even more impatient now than before. Her tolerance for stupidity, laziness and pettiness has dropped to zero, she says.

"There's so much we can't control, we should at least try to control the things we can. And life is too short to waste time."

Already fluent in Hebrew, Spanish and English -- with a smattering of Portuguese -- now she's teaching herself French.

Next up: Japanese.

Her sense of adventure, of new possibilities, has survived the bombing intact. She plans to return to her life in New York City this fall, and after that, she says, who knows?

"I want to be something and someone, so when I die, people know who the hell I was."

BY STAFF WRITER, DEBORAH FINEOLUM RAUB

Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, New York

August 2, 1998

Contact: contact92867@innocenttarget.com

Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, New York

August 2, 1998

Contact: contact92867@innocenttarget.com